Afshan Ahmed

Lebanese artist Chafa Ghaddar has given a fresh take on the art of the fresco.

To mark her Beneath Latent Skies exhibition, which runs until April 27 at the Dubai International Financial Centre, she delves into the medium at her parents’ home in South Lebanon.

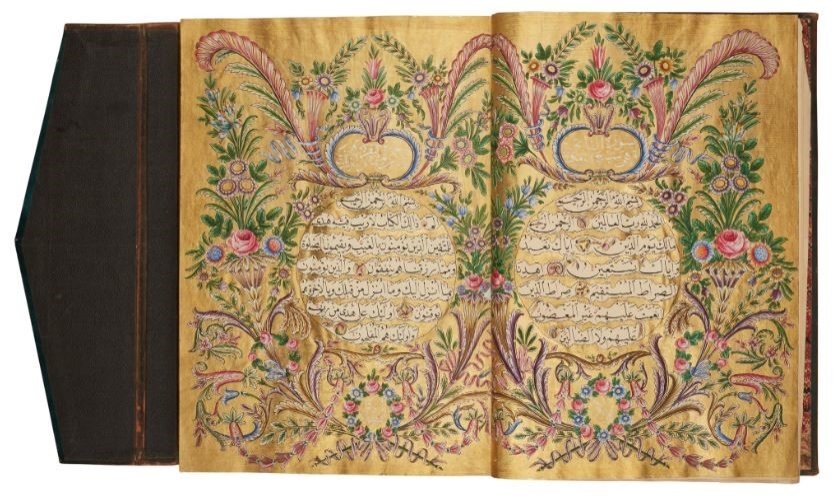

The ancestral home, she says, is the perfect analogy for her long-standing research and contemporary interpretation of this form of wall painting, in which earth pigments are painted directly on fresh wet lime plaster. It was developed in the 13th century in Italy and perfected during the Renaissance period.

“It’s a house that is strong and full of love but also one that was wounded during the civil war when we had to evacuate it in the late ’80s,” she tells The National. “Since returning, my parents have refurbished it to make it livable, but the construction was deeply wounded and is a lot weaker.

“And the walls are always subject to humidity now, which peels away every layer of paint. You have to keep healing it, priming it and concealing the surface. The house is alive; the surface has been living with us for the past 18 years, through happiness and sadness. It’s my interpretation of frescos.”

Beneath Latent Skies is evidence of the maturity that Ghaddar has witnessed in her practice since first being introduced to the concept of fresco while assisting industrial painters in preparing and plastering walls and creating motifs and decorative paintings on it after classes at the Academie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts in Beirut, where she graduated in 2009.

She went on to attend an intensive course in fresco and traditional painting techniques in Florence in 2012 and has been exhibiting works displaying her adaptation of the technique since 2014.

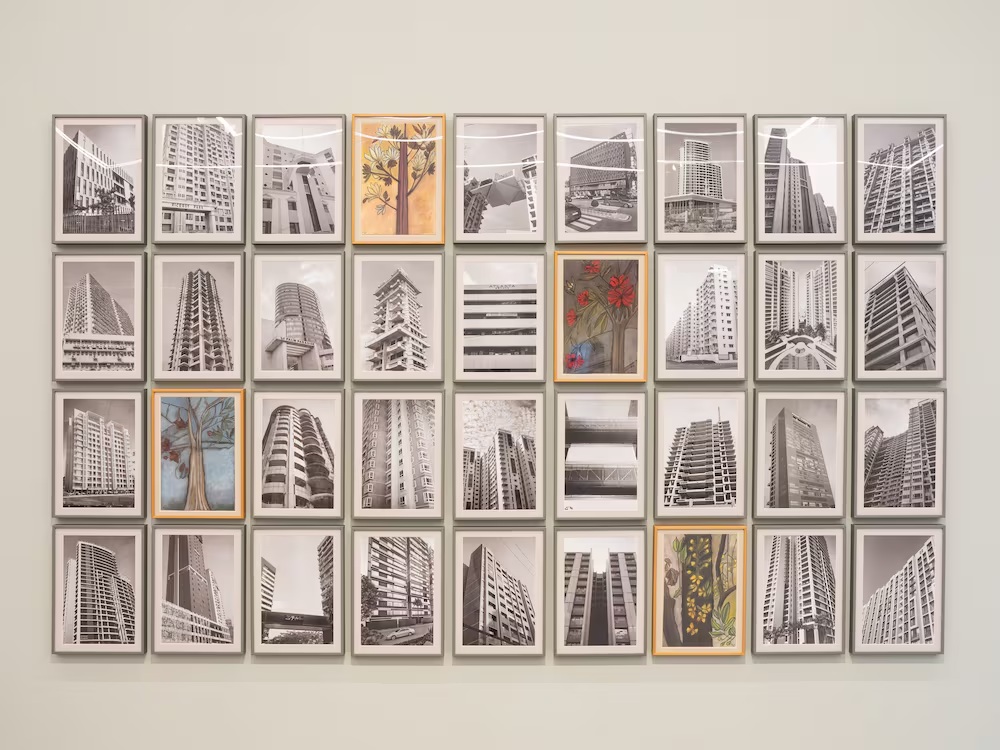

This body of more than 40 new artworks draws from the muscle memory that Ghaddar has developed over the last few years in her exploration of frescoes. It builds on that research without overthinking the foundation.

The investigation of the different nuances of the sky in her canvases, the cracks in the framed mix-media artworks that share the exhibition title, the irregularities and paintings of self in her works on wood in this exhibition continue to be a prominent departure from the classical definition of fresco and a stark reminder of its more fragile existence, and are informed by Ghaddar’s subconscious manifestations and experiences.

The works are stripped off from the wall and presented on Indian cotton paper — layered with coffee, tea and mural stucco, wood canvases with a palette of fleshy tones and fabric — before each taking on a life of their own.

:quality(70):focal(2979x1631:2989x1641)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/T23UMKKP2BBYZNDSX2UAAREMMY.jpeg?w=810&ssl=1)

“There is the entire other understanding of what a wall can be,” she says. “The layering, mural stucco, primer and protective finishing along with other preservation techniques allow me to spread the concept in a way that stands still on the canvas and experiment beyond.

“For example, you have 12 layers of stucco that are already a wall and then it is painted with lace because I am interested in the fluid aspect of a wall. It is a wall on a moving fluid canvas.”

Ghaddar says the presentation of the different hues of the sky and nature in this exhibition follows from a study that she began in Beirut in 2018, while some of the other works are a clear return to the bodily figuration, intimacy and self-portraits, which goes back to her practice in 2015.

We see a clear statement on frescos and what the idea of landscape and the sky is as a surface, and the body as a language,” she says.

Skin, a peachy-hue, site-specific installation of fabric, hangs on a metallic structure and rolls in a way that is akin to a relaxed body.

“It falls like bellies do when we sit, with all the traces, curves and marks,” she says. “These manifestations of fragility when it comes to some part of the canvas, like skin, is not degradation, rather the tension from its positioning and placement. It’s a suggestion, especially in a museum space where there is the promise of art history and preservation, of a failing elegance that is normal and marks the completeness of the works.”

:quality(70):focal(4237x2776:4247x2786)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/DTFK5TNHMBFK5J2SNU7UMVXVQE.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

The colour scheme in the paintings, with pinks, off-white and beige hues, also depict her own unease and emotions of the past three years of turmoil that the world and her country have seen.

“If you think about the last three years, the Covid lockdown, the Beirut blast and the ongoing financial crisis, it has naturally impacted our psyche and our bodies differently and on a very personal level,” she says. “So, it felt crucial to retrace the body again. And the use of the peach tones, which need to be composed with industrial pigments that are more advanced, feel like they are almost layered and contaminating the other surfaces that are more earthy and muted, making it fleshier.”

Along with the new works, which she began developing in December, the exhibition showcases her work Exhausted Forms, presented at the 16th Lyon Biennale and Corps, created in 2018.

“This show has a lot of variation in scale including works on paper and small frescoes. We wanted my first gallery show to be a comprehensive look of my practice, while leaning on some ideas more than others.”

Courtesy: thenationalnews