Razmig Bedirian

Replete with futuristic scripts, textiles and iconography, a new group exhibition in Dubai is attempting to reimagine popular views of what an Arab future looks like, using humour, symbolisms and rituals.

The exhibition, at the courtyard of ICD Brookfield Place, the Dubai International Financial Centre, requires touristic enthusiasm and some sleuth work to navigate through. And while the pieces take their cue from Arab and regional traditions, building on familiar motifs and circumstances, they present something entirely novel.

The title for the exhibition, Do Arabs Dream of Electric Sheep, takes inspiration from the 1968 fiction novel by Philip K Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which is perhaps more widely known by its retrospectively-altered title Blade Runner. However, its title and evident leap into science fiction are where the inspirations from the novel end.

“We wanted the name to convey a sense of humour and cynicism,” says curator Adam HajYahia. “It’s not coming necessarily from the book, but it does comment on science fiction narratives and traditions, and how they approach the idea of the future.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/VU25PNZ7UZFYJFYI2AIOGEC7AE.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

The exhibition features five works by six different artists, which range from films, texts and textiles to multimedia installations.

“What we were trying to do here is to think about future possibilities of being and existing together that go beyond traditional futuristic narratives that limit the future into these dichotomies of utopia and dystopia,” HajYahia says.

The works in Do Arabs Dream of Electric Sheep try to imagine a future that falls more in the grey area between these bipolar extremes. The exhibition opens with Resembling Resilience, a series of jacquard blankets by Tracy Chahwan.

The Lebanese illustrator brings her cartoonist approach and vibrancy to the textiles. She draws inspiration from the stories that traditional rugs and carpets tell but imagined what that approach would look like in the future.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PYG2XMW54VH6JBTPZ7VX2BGIRU.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

In one, three women are skydiving down to a metropolis of petal-like structures and towers. Instead of parachutes, however, they don shisha pipes on their backs, the nozels of which are spewing flames.

In another, a woman slouches over a table, smoking a cigarette. Behind her are two armed men fishing in a contained pond, from within which Beirut’s famous Rocks of Raouche loom.

“This one came to me very organically,” Chahwan says. “It’s kind of me, tired of this image. Personally, as a new diaspora, only seeing the news from home and media, it’s exhausting. We don’t see daily life. We only see misery and catastrophe. But I think when you still live there, you see the nuances and daily life.”

“The futurism aspect [in the work], for me, is more of a critique,” Chahwan says.

Now living in the US, Chahwan says she was taken aback when she visited Lebanon last summer to find that, while many were struggling to get by in the wake of the port explosion and the economic meltdown, there were also those who were also living relatively blissful and unaltered lifestyles.

“When I went back, there’s a lot of misery but there’s still pockets that are living in a niche,” she says. “There are people living in pristine cleanliness next to something completely destroyed.”

With Fono-type, Akakir Studio — the Paris design studio of Algerian artist Walid Bouchouchi — presents 45 posters, each dedicated to a particular letterform of a newly-envisioned script.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/SENGWMGVMZFSJJGHYLNF4GP3QA.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

“He works out of visual language and what visual language and aesthetics can offer,” HajYahia says. “He comes from a background in graphic design. Here, he tries to talk about his personal experience as an Algerian post-independence, living in a post-colonial nation-state where there’s a mix of different cultures who speak Arabic, Tamazight and French. So how can you think about a way of communicating in a post-colonial nation-state, where there is no purity of a pre-colonial reality and a contamination of post-colonial reality.”

The next installation attempts to steer away from language as the principal mode of communication and offers something more rooted in image and symbolism.

Large-scale banners hang from the ceiling, billowing with the fans set underneath. The banners are vibrantly coloured with neon pinks, yellows and pastel blues. They display images that seem familiar, Arabic numerals and letterforms besides pictures of storks and people.

For a better understanding of the stories the works suggest, the screens, positioned underneath by the fans, break down the symbolism of each banner.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/W2JWMTS7HVFZ7FR3HUXH4XMMEY.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

“It began really with examining flags of governments,” the artist Haitham Haddad says. “I always wondered whether we could use them as a way of communicating. In my work, I generally start by creating a story before saying what I want to say. I asked myself how we can communicate without language.”

The works build a unique set of symbolic semantics.

“In every screen, I explain everything. They are indexes,” Haddad says. “You’re walking in a colourful place and the screen beneath you gives you explanations. The flag suddenly has new meaning. The flag develops with its connection with you.”

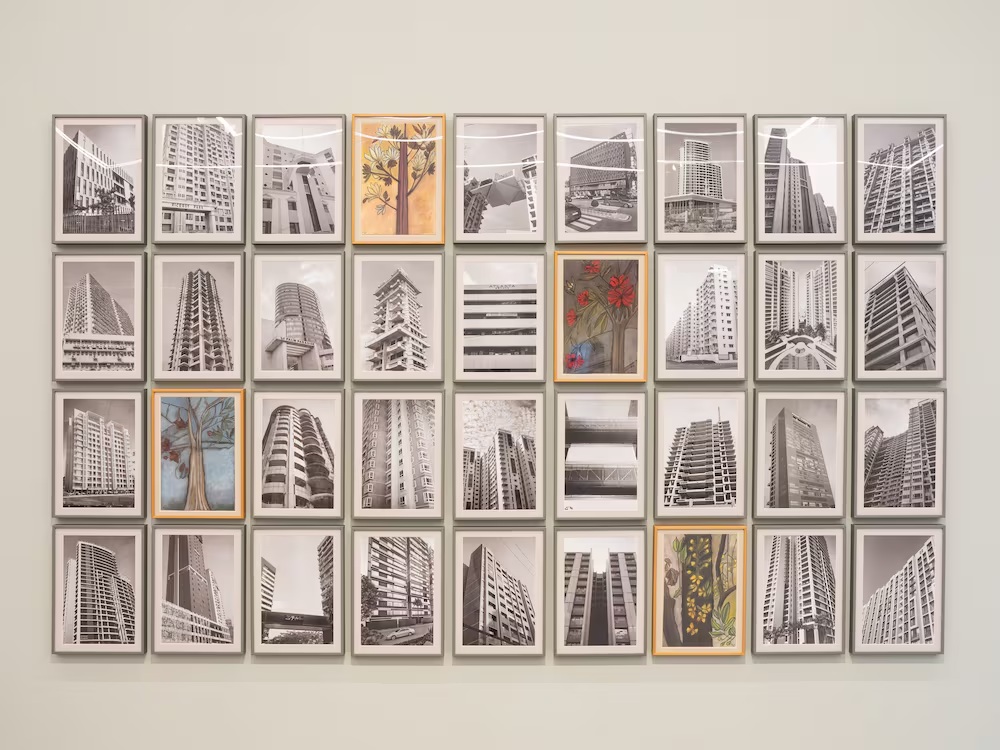

The exhibition’s final two works include Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s piece, which is titled At those terrifying frontiers where the existence and disappearance of people fade into each other.

It is a video and panel installation that fills the room. While many sci-fi narratives of the future in the West are often sparked by a catastrophe, many Arabs have already undergone this cataclysm in a way, it suggests.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/TAROCSV56RGYXPMJBEDX7LPETM.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

“They have a very interesting practice of mixing sound, video image and all sorts of objects in an installation,” HajYahia says.

“This particular work is a repurposing of Edward Said’s After the Last Sky, which is a book about Palestine that is quite poetic. They take different segments of the texts and turn them into a song. The avatars that you’re seeing are made by an algorithm that traces different faces, almost in the way military profiles.

“They take the images found on the internet of people who marched in Gaza in 2014. The artists couldn’t be with the marchers. They’re singing the song that talks about fugitivity, and about being a refugee, about being in the negative, which is a recurring theme in their practice.”

The final work is Party on the Caps by Meriem Bennani. It is a 25-minute HD video of an imaginary island in the future called Caps, short for capsule. The island is a holding space for people who try to teleport into the US.

“People who try to migrate to the US are intercepted and sent to this island where they cannot leave. It actually builds on these funny and overproduced notions of futurity,” HajYahia says. “It uses it powerfully and vibrantly to talk about migration. Within this island, she specifically focuses on people who migrated from Morocco and were intercepted into the Caps.”

The characters in Party on the Caps include a woman who retains the songs and music of her native Morocco and performs them for others on the island. Another is an MC who makes songs about French fries with troopers walking around him. A third is a woman, who is celebrating her 80th birthday, yet looks only a fraction of her age.

“It talks about migration from the perspective of the body, like how being intercepted affects you physically,” HajYahia says.

Courtesy: thenationalnews