Maan Jalal

Renowned Iraqi artist Afifa Aleiby’s solo exhibition at Zawyeh Gallery in Alserkal Avenue is a captivating journey across various narratives, centred on female figures.

Titled Timeless Echoes, the exhibition, which runs until May 8, includes Aleiby’s latest pieces. Almost a year in the making, the show explores a number of societal themes through women in various states, from peaceful and meditative to forlorn and grieving.

Throughout her career, Aleiby’s canvases have been dominated by female figures. It’s an element of her practice easily misinterpreted as a deliberately feminist point of view — one that Aleiby makes a point to correct.

“I consider the woman an important element in my work not because I’m a feminist,” Aleiby tells The National.

“The woman is important to me because, through her, I can express my ideas. The way she sits, her poses, the way she moves her hands, her gaze, all of these elements are important ways to express my ideas.”

Aleiby’s study of the female form connects her to a deep tradition of depicting women, which she believes is indicative of the enigmatic and universal influence women have had throughout many civilisations.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/V45JCHLF2NCT7PCWAFLLOXWLDU.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/65ONNWPT5FHJTA2MZRKYDBT56U.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/XLQN65GZZZA5PPHXZLONNQ6HI4.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/FLJH4RQG5REMBAOHTLARLBTP4A.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/NYKUG4VAWVGHFILHH6C6C5P2ZY.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/SP77PNA6ZZFSHLPVBAGQKEAXDE.jpg?w=810&ssl=1)

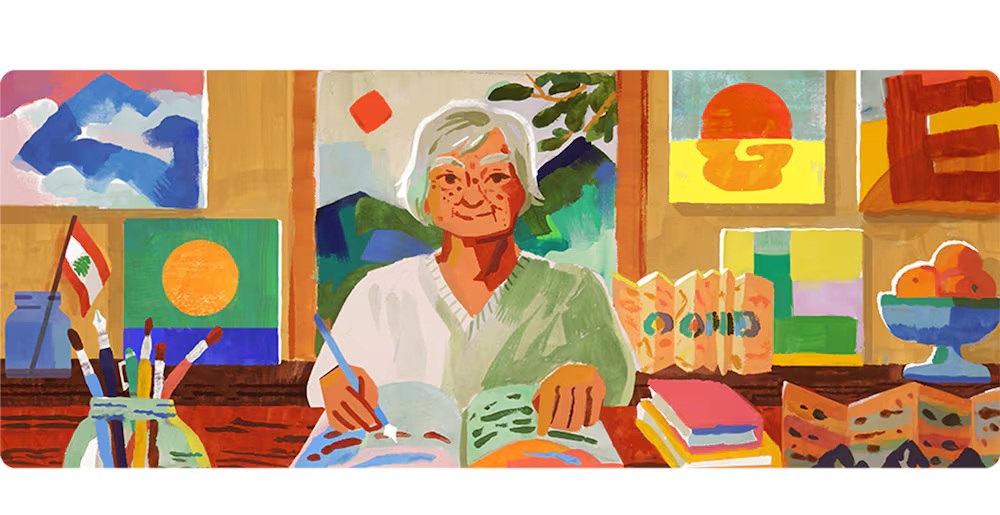

Afifa Aleiby’s female figures are painted thoughtfully, with extreme care. All photos: Khushnum Bhandari / The National

“What has been the most important figure across the history of figurative art even from the stone age? The woman,” she says.

“This figure that can create another person, give birth and breastfeed a child, this figure who has other beautiful characteristics, which are not possible to describe, all of these are the essential elements that made the woman incredibly important in the history of art.”

Aleiby’s perspective as a woman adds a unique element to how she depicts the female form and experience. Her figures are painted thoughtfully, with extreme care. Their faces are well-defined, their bodies formed of pronounced shapes, and the details of their dress are graceful, elegant and reveal Aleiby’s precise yet tender hand.

There is also a narrative quality in her work. Viewers are given detailed glimpses into Aleiby’s figures, as characters in a much larger story. Whether pensively staring out of a window, asleep on the grass or playing a flute on a cliffside, they are buoyant and light, yet rooted in their space and environment.

Motherhood is a strong theme in the exhibited paintings, with four of the nine pieces depicting a mother and child in different stages — pregnancy, infancy and death.

One painting At the Spring shows a mother holding her son, reminiscent of Michelangelo’s seminal sculpture Pieta, while also referencing elements of Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks.

In another painting across the gallery, titled The Rape of Baghdad, a woman cradles her grown daughter, while American tanks move in the landscape behind them.

Both works, while visually distinct, are connected through the subject matter of a mother’s loss and grief.

“It wasn’t until I had a child that I realised the tragedy of the world,” she says.

“When I gave birth to my son and held him in my arms, this innocent being in this world filled with filth, I felt a lot of pain and an extreme sense of fear. It was the first time in my life that I understood the meaning of fear. It stays with you, this fear. Even today, I worry about him, even from a strong gust of wind.”

Aleiby’s son is artist Athar Jaber. His practice explores the contrasting conditions of beauty and violence through sculpture. Aleiby herself comes from a family of artists — her brother is the renowned painter Faisel Laibi Sahi.

Born in Basra, Iraq in 1953, Aleiby grew up in a home where art and art history were both accessible and encouraged. She explains that her exposure to art through her family was organic and that she developed knowledge and taste from a young age.

“I developed a sense, whether I was aware of it or not, of what I liked and what I didn’t, what spoke to me and what didn’t,” she says.

After studying at Baghdad’s Institute of Fine Arts, Aleiby left Iraq and trained in Moscow, before going on to live in Florence in Italy, Yemen and eventually settling in the Netherlands.

Aleiby continuously studied art, and cites the early Renaissance Italian painter Sandro Botticelli and the late 19th-century French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as great influences on her work.

Going beyond them, Aleiby has taken the voices of many, melding them into a visual language that is instantly recognisable as her own.

Her sense of harmony, solitude and pictorial balance is remarkable. There is no melodrama in her work but a resilient state of being that also comes through in her technique and dedication to form and unity.

In all the important ways, Aleiby’s work exists outside labels such as feminist, Iraqi, Arab or any other reading that can make art feel overly constructed, restrictive or even reductive. They are labels that Aleiby herself isn’t interested in.

“I consider myself an artist, a painter” she says.

“Art doesn’t have to belong to a specific place, a specific community, a specific culture. Art is global, it’s humanistic, it speaks to all of humanity.”

Courtesy: thenationalnews