Monitoring Desk

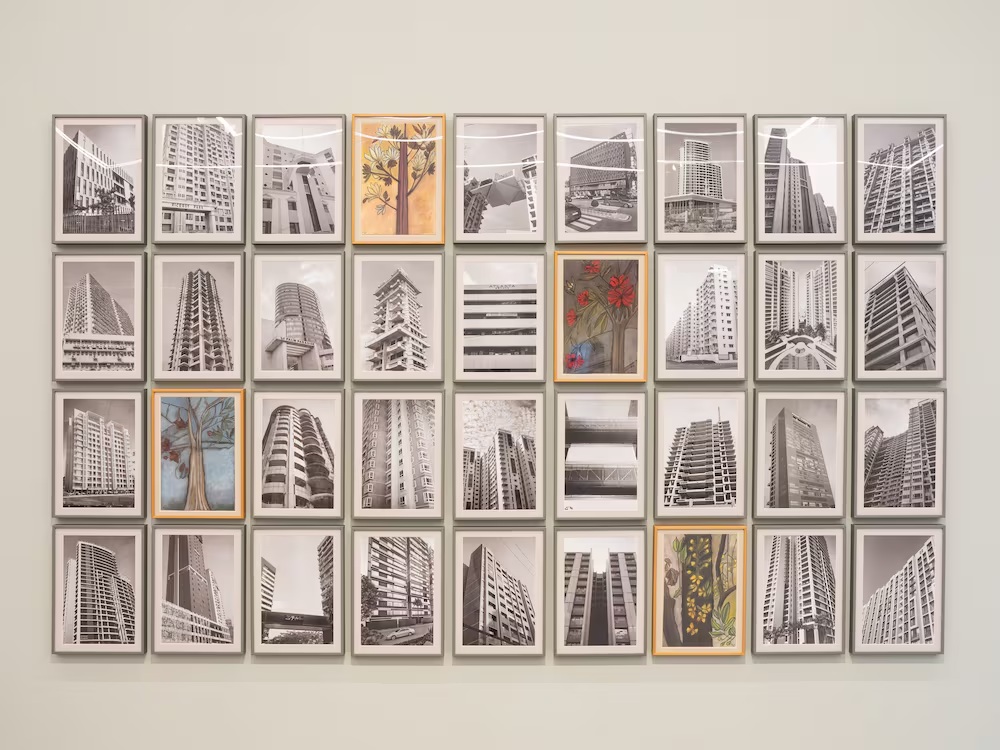

A vast group show, including works by nearly sixty artists, spreads across two floors of Arter’s interior, where the overall theme showcases the creative diversity of fun and games, revivifying art world professionalism in the process

The cold, postcolonial shell of museum whiteness can be deadening to public morale in the face of worldwide calamity and local displacements, firming up the hard, infertile soil on which the cause of culture rests, as it were, in the eternal sleep of institutionalization, like a body flown out to deep space in a cryogenic cell, light-years away. The answer from leading, traditional establishments as the Louvre, Tate and the Met, has been to deaccession in response to international calls for the old Eurocentric guard to put down their shields and give back the treasures their colonialist forefathers stole.

And as masterpieces of art by the world’s Indigenous Peoples art leave their vitrines and collections where they’ve enriched the wealthy, leisure classes who’ve relished in the fruit of their imperial acquisitions, a rage of artists has come to claim that empty space motivated to create new works and relations in the spirit of independence and occupation, to redirect the runaway train of civilization from collision to flight, within, and without the trappings of history. That is, in effect, where art comes in, as a discipline that, while not immune to the traumas of the past, serves as a bold and refreshing empowerment of the present moment.

An object, like a word, when completely on its own, is irrational in its perfect holism. Only in terms of connection, context, does meaning evolve. Later, semantic and semiotic value changes over time according to its usage, as is socially predicated. Any single thing, a word, an object, is unreliable, indefinable, unless it is acted upon. That inaction, however, and impracticality, has come to be a signpost for the definition of art, as exhibited in its various mainstream institutions. Museums, for example, are places of distance from objects and what images or concepts they represent, what media they abstract.

In some cases, performances bridge the gap between seer and what is seen. The idea of a performer, or actor, though, is open to interpretation, as the act of seeing is conditioned by the curation of the works. Direct interaction, then, is perhaps the last and most intimate step in the exhibition of art, before it cycles around back to collaboration, and the creative work of the artists themselves. This is a question that collectives have raised, especially in the wave of social artwork that emerged out of societies on the fringes of Europe like Yugoslavia with the group Škart, and, of course, elsewhere.

To hint at laughter

Unexpectedly, to some, while obvious to others, the seemingly rigid bearings of Arter are home to a diversity of experimental visions with respect to art’s relationship to general society, as it inspires its workers to engage with the general population, children and the working-class, so that they might let their worldly presumptions down, like their hair, and lighten up in front of a late-night game in the light of day. A piece by Swedish artist Jacob Dahlgren starts the show, “ThisPlay,” from the top down, curated with a taste for disparate resonation by Emre Baykal, as its readymade dartboards, combined together, form the likeness of a pop-art painting.

Dahlgren began his artistic work in abstract painting, incorporating geometric forms and everyday colors. A player might walk over to his work, “I, The World, Things, Life” (2007), and pick up five darts, and allow their mind to be subsumed by the visual field of concentric yellow and black circles. In an adjacent room, a reworked ping-pong table by George Maciunas, a key figure in Fluxus, is almost unplayable, its paddles stapled with bottle caps or topped with cleaning brushes. The subversion of logic for joy, the competitive wheels of capitalism for the square tires of parody, is arguably the chief raison d’être of the contemporary artist.

Arter, and Baykal’s curations, in particular, are rife with references to the history of Fluxus, integrating works by pioneers like Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik into what appears to be a visible majority of its group shows. “ThisPlay” is no different, and encompasses a mass representation of artists way outside of the everyday local Turkish art scene, with a welcome turnout from less-traveled European countries like Finland, Iceland, Bulgaria and Serbia. That said, the show features characters who commonly reappear at the center of the art map in Istanbul, like Cevdet Erek, Deniz Gül, Leyla Gediz, Füsun Onur, Nilbar Güreş and others.

The surfacing of Onur’s artwork demands a special highlight because she will be representing Turkey at the Venice Biennial of 2022, in an event that will be historically charged with post-pandemic fervor. The upwardly mobile bound to collect, and the stylish fixations of the global art crowd can expect to gawk in awe at the midcentury feminism of Onur, whose installations conjure the conceptualist fantasy of spatial reinvention, guiding perspective from individuality to mutuality with a liquid, aural aesthetic. If her last solo show, “Opus II – Fantasia,” at Arter, was intellectually opaque in its blankness, her work at “ThisPlay” is more approachable.

Şakir Gökçebağ, “Prefix & Suffix 1,” 2010, installation with umbrellas. (Photo by Matt Hanson)

From work to play

As a sly comment on durational art, and even performative action, Onur’s eight-hour video, “Pink Boat” (1993 [2014]) begins when Arter opens, and ends when the elaborate building in Dolapdere closes. It is a subtle piece, demanding the kind of patience that is as rare in such a place for skittish human attention spans as seeing a wild jungle cat. But, imaginably, when the video came out in 1993, after Onur had already made a good name for herself, it is not entirely impossible that there were people who sat through the whole length of it, watching the strong currents and winds on the Bosporus pass over a pink boat in its waters.

As a site-specific artist, Onur’s video reflects the sense of time that museums condense as a voice-over plays on loudspeakers announcing intervals prior to its closure. Her other works are as uncanny, like “Water by the Sidewalk” (1981), a plexiglass collage of artificial spillage against the side of a wall, which is reminiscent of the tone in artwork by Ayşe Erkmen, her peer, whose piece, “Colours of Letters” (2006) is a childlike evocation of her career-long penchant for using plexiglass too, although tinted and often warped. There are a number of ladders in “ThisPlay,” with multicolored or missing steps, mirrored. Where they lead does not matter.

Courtesy: Dailysabah

The post On art as diversion: Arter exhibits ‘ThisPlay’ appeared first on The Frontier Post.