MELTEM SARSILMAZ

Dubbed the world’s only iron church, the Church of Sveti Stefan is a Bulgarian architectural complex sitting on the banks of the Golden Horn in Istanbul. Let’s take a look at the history of the structure spanning more than 100 years as well as its architectural details

Balat is an architecturally mesmerizing Istanbul district that takes you on a historical journey with its colorful buildings, synagogues, churches and mosques between the Ayvansaray and Fener neighborhoods on the shore of the Golden Horn. The district is named after the word “palation,” which means “palace” in Greek, due to its proximity to the Palace of Blachernae, located near the city walls.

When you visit Balat, a historical building awaits you at every corner. With its long slopes and structures in a range of architectural styles, it provides you with the opportunity to capture spectacular photographs while embarking on a mystical historical journey. Down one of the slopes of the district, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church of Sveti Stefan, also known as Iron Church, welcomes you.

From priest’s house to church

Historical buildings are important not only for the sake of architecture but also for social and historical events. Witnessing many incidents throughout history, they may even become the protagonists of some events. The Church of Sveti Stefan is one of those important historical buildings. Let’s take a look at the social events that took place up until the church was built.

The Ottoman Empire ruled the non-Muslims in its territory with a system called the “millet system.” According to this system, non-Muslims in the Ottoman lands were divided into three nations as Greek, Jewish and Armenian. Namely, they were classified according to their religion, not their ethnicity. Christians were also divided into two groups: Greek and Armenian. The religious and administrative responsibility of all Orthodox were in the hands of the Greek Patriarchate (Ecumenical Patriarchate). The patriarchate was the authority to which the Orthodox would apply in case of any problem. Since the Bulgarians living in the Ottoman lands had no religious and political representatives, their representative against the state was the Greek Patriarchate, as well. However, Bulgarian subjects complained about the Greek Patriarchate, which was in control of the religious administration. The Bulgarians were writing complaints to the Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman Empire, about the forced assimilation and oppression under the Greek Patriarchate. The use of the Greek language for lessons and rites in schools and churches was one of their main complaints. They also wanted the Ottoman Empire to protect them in their complaint petitions and conducted various studies on this issue until they got results.

Bulgarian-born state official Stefan Bogoridi (Stefanaki Bey) was among the citizens of Bulgarian descent who carried out important works to escape from the oppression of the Greek Patriarchate. The Ottoman Empire allowed him to establish a place of worship for the people of Bulgarian origin. For this place, Stefan Bogoridi donated his house, which was reorganized as a wooden church for Bulgarians, and the foundation of the Bulgarian Exarchate was thus laid. In 1858, with an edict, the Bulgarians were allowed to build a new church in place of the wooden church but its construction could not be realized because the ground was not solid. Therefore, the construction of the new church was shelved until the building of the Iron Church.

On March 11, 1870, Sultan Abdülaziz issued the Exarchate Edict, which accepted the Bulgarians’ desire to establish an independent church. According to the edict, the Bulgarian Exarchate was recognized as an independent institution. After the wooden church suffered from a fire, it became necessary to build a new structure in its place despite the weak ground conditions. Therefore, an iron frame was preferred over concrete reinforcement.

The Iron Church, which cost 4 million levs at that time, was actually completed in 1896. However, it was blessed and launched for worship by Exarch Joseph I in 1898 after the redesign of the iconostasis. The bust of Stefanaki Bey, who made great efforts to open the church, was also placed in the garden of the church.

Architectural features

The most important feature of the Church of Sveti Stefan is that it is completely made of iron. A total of 500 tons of iron was cast for the parts of the church. The casted parts were brought from Vienna by ships via the Danube and the straits.

The architect of the church was Hovsep Aznavour and the manufacturer and construction company was Rudolf van Wagner, operating in Austria. The church, which features neo-Gothic and neo-Baroque architectural elements, also carries traces of the modern Renaissance style.

The bell tower of the church, whose altar faces the Golden Horn, is above the entrance door. All of the six bells in this tower, which is 40 meters (130 feet) high, were cast in Yaroslavl, Russia. Two of six bells are used today. The exterior decorations of the three-domed and cross-shaped church are fascinating. Just above the entrance door, you can see a sign representing the Trinity – Father, Son and the Holy Spirit – universe and sun.

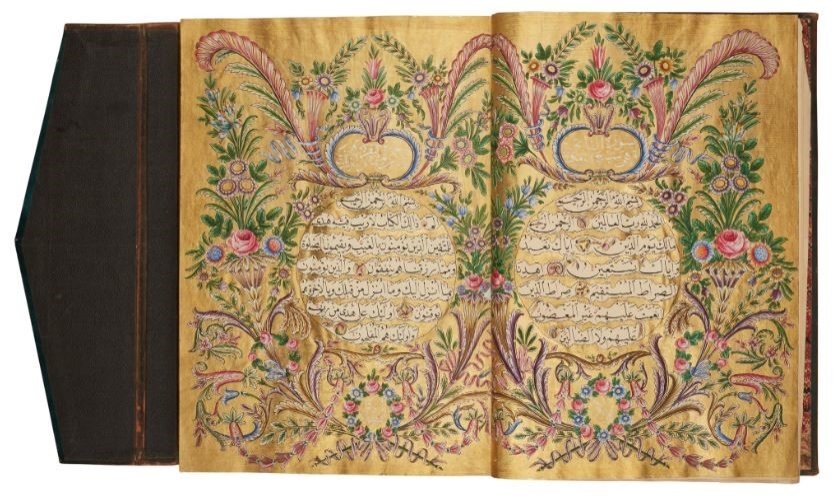

Inside the church, the wooden iconostasis, which was also made in Russia, Moscow, also attracts attention with its standout icons. The icons depict many figures from Virgin Mary to Jesus, from Archangel Gabriel to saints Cyril and Methodius. The painted windows of the church also make great ambiance by the sun.

Restoration

In present days, the iron church stands out as a testament to the architecture of Bulgaria and Turkey. Following seven years of restoration, the church was reopened in 2018. With a capacity of 300 people, the church has stood like a pearl on the Golden Horn with its fascinating beauty for 124 years. Of the three iron churches in the world, the only surviving church is Sveti Stefan. If you happen to be in Balat, you should definitely visit the church by descending the hill between the historical houses.

Courtesy: Dailysabah

The post Istanbul’s Sveti Stefan: The world’s only surviving iron church appeared first on The Frontier Post.