Vittoria Benzine

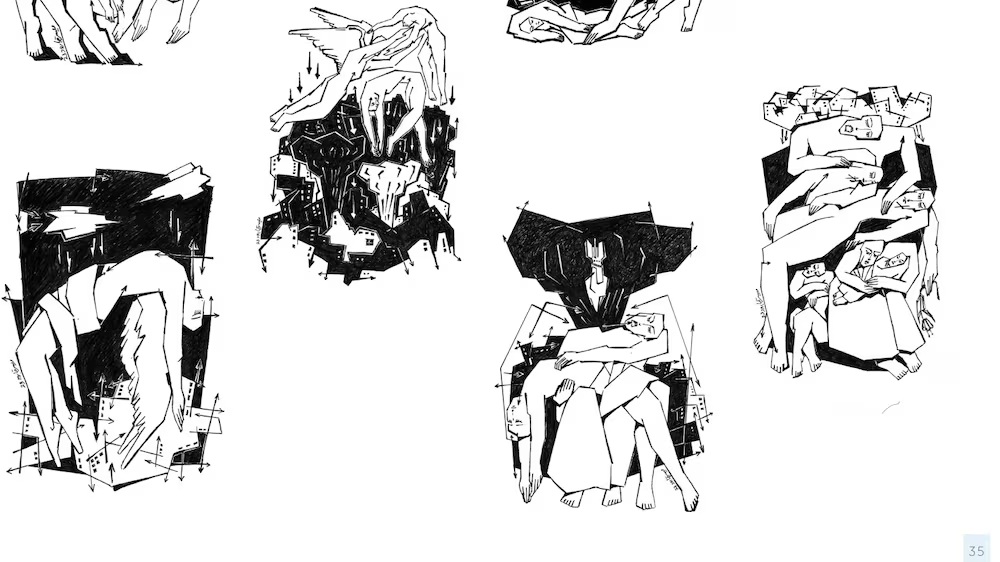

Across Azzah Sultan’s Batu Belah, Batu Bertangkup: The Devouring Rock at Trotter & Sholer, bright patterns flower from canvases featuring the silhouettes of two women, their faces replaced by petals and their hair covered with batik fabric from Southeast Asia.

Sultan’s latest exhibition explores a classic Malaysian folktale of the same title, which warns children against the perils of selfishness. The story predates written record, passed down from one generation to the next through oral storytelling. Sultan’s version shifts focus from the moral to the mother-daughter relationship, which unfolds across six uniform canvases with wall texts that recall subtitles. These artworks portray the story with individual scenes animated by the visual relationship between the colorful batik fabric and oil-painted patterns mimicking the material.

Like most versions, Sultan’s story opens with a struggling single mother named Mak who fishes to feed her two children. One day she hits the jackpot: a mudskipper filled with rich roe, reimagined here in pearls. Sultan’s first canvas, “Don’t forget what I’ve told you.” (all works 2021), depicts Mak entrusting her daughter, Melur, to prepare the roe for dinner. Melur’s brother devours it all, as Mak discovers in “You’re unreliable, you couldn’t save some for me?” Distraught, Mak runs to the devouring rock, which swallows her whole. In the pivotal scene, “Please let my mother go.,” a cascade of iridescent fabric twists toward the floor, the remnants of Melur’s devoured mother.

Where the story Batu Belah, Batu Bertangkup traditionally promotes virtue by emphasizing Mak’s death, Sultan’s work questions whether a moral founded on guilt can yield positive outcomes. The artist herself has experienced pressures like Melur’s in “Mak, don’t talk like that.” by assuming the burden of consequences she didn’t cause. Stories that last tell stories about us.

The characters’ silhouettes are differentiated by their color palettes: Mak is rendered in warm tangerine, Melur in phthalo blue. Omitting faces better enables viewers to project themselves into the story. Hands serve as the primary narrative vehicle: capable, dynamic, and large — but also based on photos of the artist’s own hands. Melur’s distraught attempt to grasp at thin air in “Wait for me!” conveys emotion more powerfully than facial expressions.

The concluding installment, “Not my burden to bear.,” portrays Melur head on for the first time, gold lace igniting her black hair. With this final stand, Sultan reframes the story’s conclusion as one of liberation rather than mourning. Melur acknowledges the tragedy while absolving herself of responsibility for her family’s circumstances and her mother’s death. Through this revelation, Melur becomes a more complete person, entirely herself.

Sultan and I spoke at the DUMBO studio she’s worked in since starting a residency with PioneerWorks last October. The artist showed me a photo of her first painting to feature hands, a self-portrait from 2013 in a pose of supplication. For the first time, she noticed the similarity between her gesture and Melur’s.

In some ways, these artworks embody the relationships they depict. There’s a performative quality to their maximalism, their orchestrated cacophonies of color punctuated by expertly shaped fabric. Sultan gained her first appreciation for batik from her mother, who held fashion shows with the material wherever they moved, from Malaysia to Bahrain. “The way I dress, the way I see color and patterns, is because of my mother,” she told me.

For the artist, incorporating batik fabric into this work constitutes an homage, but a considered one. It’s also a carefully stitched act of love that acknowledges the power of these stories we tell ourselves and each other, and our power to change their meanings.

Courtesy: hyperallergic

The post An Artist Shifts the Focus of a Folktale from Guilt to Liberation appeared first on The Frontier Post.